All The Ways Are His

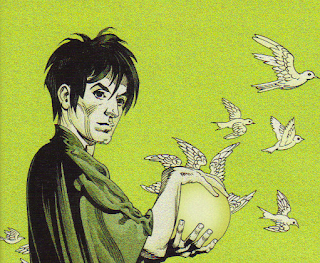

This in reply to a young monk asking, “I seek the King of Dreams. Am I going the right way?” The exchange comes in the middle of an astounding dream sequence, across pages of silent, exquisite narrative. We witness the monk traverse a midnight void on a sparkling bridge. Or is it a river, for he soon must leap from a yawning golden cataract. When he drifts to a halt, his wood-block sandals meet a jagged jade landscape, where they soon disintegrate. From there, a bleached bone-yard of fantastic remains, and a garden of whispered contradictions.

Even if the names Neil Gaiman and P. Craig Russel mean nothing to you, opening The Sandman: The Dream Hunters graphic novel makes you one lucky lemur. As I said, the scene above is a fantasy within the fantasy. I belabor this because both artist and writer have been floating gargantuan ideas for decades. It’s probably more challenging for them to craft the mundane.

Novelist and comic-scribe Gaiman reinvented DC’s Sandman for mature audiences in 1988. The character went from being a Depression-era vigilante to a deity whose “adventures” spanned time, space and literature. Ending in 1996, when Gaiman left, The Sandman might be the most widely-acclaimed ongoing comic ever; it ranks high among readers who like The Watchmen, high-flown indie fluff, and little else.

I can take or leave Gaiman’s novels, dripping with >kewt< as they are. The voice of his comics, however, when paired with the perfect artist, is irresistible. For The Dream Hunters, he crafts a faux Japanese legend about a monk who falls in love with a fox. Originally this tale had been published as prose, with illustrations by the inimitable Yoshitako Amano (Final Fantasy). But thankfully Russel couldn’t get the imagery out of his head, so here we are.

I can take or leave Gaiman’s novels, dripping with >kewt< as they are. The voice of his comics, however, when paired with the perfect artist, is irresistible. For The Dream Hunters, he crafts a faux Japanese legend about a monk who falls in love with a fox. Originally this tale had been published as prose, with illustrations by the inimitable Yoshitako Amano (Final Fantasy). But thankfully Russel couldn’t get the imagery out of his head, so here we are.

In the 1970s and 80s, adapting the work of Rudyard Kipling and Michael Moorcock, Russel wielded an intimidating baroque style. He’s since become a storyteller of startling balance; his panels no longer paralyze the eyes with detail, but draw them further in. Forest landscapes offer lushly-lined foregrounds that give way to mountains and clouds of hypnotic simplicity. All of these, including water courses, crisp and curl like Japanese block-prints of old. The coloring by Lovern Kindzierski, too, is in homage to this bygone era, as is the texture of watercolor paper, added digitally.

While it would be easy to gush over the storybook elegance of every panel (and their marvelous interaction on every page), there are highlights. One is the scene in which a demon tears free a piece of the monk’s shadow. The piece is then ground up and used in an incantation by the small and jealous onmyoji, whose material wealth has failed to settle his soul.

Another great scene has the fox, who can craft elaborate illusions, dangle herself before the onmyoji as a beautiful young woman. She lures him from his wife, concubine, home and possessions on the promise of filling his existential chasm. During the meal they share, he experiences a lavish home and delicious food. The reality the fox hides, of a derelict shack and bowls of mice, unfolds chillingly. As usual, the Sandman appears late in the tale, as Gaiman’s characters reach never-forced, poetic crossroads.

Another great scene has the fox, who can craft elaborate illusions, dangle herself before the onmyoji as a beautiful young woman. She lures him from his wife, concubine, home and possessions on the promise of filling his existential chasm. During the meal they share, he experiences a lavish home and delicious food. The reality the fox hides, of a derelict shack and bowls of mice, unfolds chillingly. As usual, the Sandman appears late in the tale, as Gaiman’s characters reach never-forced, poetic crossroads.

As a cape-chaser, an action junkie, I found The Sandman late in my reading life. I decided to finally read him not because someone forced me to, or spoke so eloquently about his travels that I couldn’t resist. No. I entered his world simply because nobody could describe it. Here, I’ve done The Dream Hunters hardly any justice. But sometimes you just want to say, “Thank you.”